1924

Clifford

2017

Clifford Gaddy

August 1, 1924 — December 7, 2017

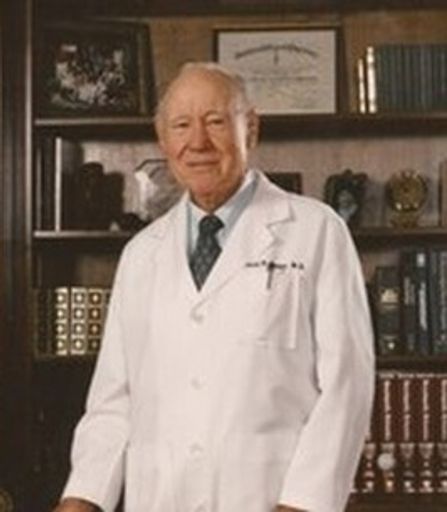

Clifford Garland Gaddy, M.D., 93, died of natural causes Wednesday, July 12, 2017, at his home. His death follows by only a few months that of his much loved wife of 71 years and best friend, Inez Chapman Gaddy. He was born January 8, 1924, in Lake View, South Carolina, a son of Finn Duncan and Orilla Lupo Gaddy. After graduation from Lake View High School at age 16, he attended Wingate Junior College and Wake Forest College. His undergraduate studies at Wake Forest were interrupted by military service in World War II. He was released from service after a year and a half to enter Wake Forest’s Bowman Gray School of Medicine in Winston-Salem, NC, where he received his medical degree in 1947 at the age of 23. While in medical school, he married Inez. Following a year of cardiovascular research in the Department of Physiology at Bowman Gray, he began his graduate medical studies at the University of Virginia Hospital in Charlottesville, VA. There he completed his internship and residency in internal medicine, as well as a fellowship in cardiology before becoming an instructor in the Department of Medicine. In 1952 he moved to Danville, VA, where he began a solo practice in internal medicine and cardiology. In 1964 he was joined in the practice by Dr. Edwin Harvie, who remained a partner and dear colleague until Dr. Gaddy’s retirement in 1999. During that long career, he was a member of the American Society of Internal Medicine and served on the board of directors of the Virginia State Society of Internal Medicine. He was a fellow of the American College of Physicians and a member of the Virginia State Medical Society, the American Medical Association, and the American College of Cardiology. He also served as president of the Memorial Hospital Medical Staff of Danville and president of the Danville-Pittsylvania County Medical Society. He was a consummate physician. No interest in his life was older than his love for medicine. In the book he wrote in 1993, Triple Coronary Bypass: A Cardiologist Tells You about His and How to Prevent Yours—a book that combines a detailed account of his 1992 near-fatal heart attack with reflections on his life and career as a physician—he wrote: “I can’t remember when I didn’t want to become a doctor. I must have been in elementary school when I ordered from a magazine a copy of a book called The Modern Home Physician. I had answers to medical problems that other kids didn’t know.” His original intention was to add a Ph.D. to his M.D. degree and then pursue a career in medical research and teaching. Luckily for the thousands of patients he would care for later, clinical medicine drew him away. His interest in the academic side of medicine never waned, however. He was an avid reader of the latest medical findings and himself contributed to the medical literature. He constantly tested himself by studying for board certification (even when not required), and he never missed an opportunity to teach others—whether other physicians or nurses or other personnel. But clinical medicine evoked a passion that exceeded that for the laboratory or classroom. His dedication to his patients was the hallmark of his career as a doctor. Long after anyone could count on a physician to do so, he continued to make house calls, driving late at night far into the counties surrounding Danville in all directions (often with one or more of his children in the back seat) to tend to patients who had no other access to care. He wrote, again in Triple Coronary Bypass: “The practice of medicine has had its long hours and stressful times for me. This was especially true in the days of my solo practice, my first twelve years of work in Danville.” Still, he went on, making those house calls was satisfying: “Appreciation for my services was great. Sometimes the compensation was a bushel of apples just picked from the orchard, or a fresh tenderloin steak. In those days almost no one had medical insurance but no inquiry about compensation was made. For rural patients payment was often made when the season’s crops were sold. I had no liability insurance and no thought of any form of litigation ever passed through my mind. It was a great era in which to practice medicine.” Later, even when it was impossible to ignore the creeping legal and bureaucratic shackles being placed on physicians, he continued for as long as he could to follow the principles of that “great era” of medical practice. It is for precisely that attitude that he is remembered by so many in the Danville area. He loved medicine, and one of the greatest sources of pride in his life was the fact that he had both a daughter and a granddaughter who chose to follow his footsteps to be trained as physicians at Wake Forest. There is no doubt that some of that special fondness for his rural patients stemmed from his own background. Clifford Gaddy the physician was from birth a farm boy. He grew up on a modest farm that had belonged to his family since the time of the American Revolution. Everywhere one looked in the communities of South Carolina and North Carolina around his home, there were farms owned by Gaddys and Lupos. He reported that his special job on the farm from the earliest age was to feed the pigs and chickens and care for the ones that were sick. And to pick cotton: he wrote in his army diary that on one of his brief leaves home from the army, it was cotton-picking time, and so he joined in. Farming was in his blood, and not long after moving to Danville—as soon as he found the resources and opportunity—he bought himself a farm in Pittsylvania County. That purchase predictably exposed him to good-natured ribbing from his brothers at home in South Carolina, who never failed to call their little brother “the gentleman farmer.” But for him and his family, Westridge Farm was a very special place. For at least a few hours on Wednesday and Saturday afternoons, it was where his children could be sure to be able to spend time working and playing and learning at their father’s side. Later, in 1988, with their own children grown and raising families of their own, Clifford and Inez moved into a beautiful new home they had built for themselves at Westridge. From then on, it was above all the grandchildren who could enjoy the farm and the company of their grandparents. Westridge Farm was about family for him, but also about being outdoors and engaging in physical activity. As a doctor, he recommended exercise for his patients. As a young man he had exercised strenuously for boxing, a sport at which he excelled. In college he won the Southeastern States Golden Glove championship, and he continued to box while in the army. But he gave it up after medical school, and in later years he candidly admitted that he thought that “exercise can be somewhat boring.” The farm boy in him clearly thought that digging, raking, chopping wood, or weeding were more meaningful, and otherwise, as long as he had to keep up with four young sons, and then two daughters, he felt he had no concerns about too little physical activity. As a result, with the exception of the occasional tennis game, he did not engage in any sport until he took up golf at age forty-five. Golf became a passion for him. Perhaps it was because he suspected he would love it so much that he waited so long to take it up. He was afraid it would take time from the family. “I had seen too many golf orphans,” he noted. Now golf competed with the farm work for his scarce spare time. In his typical fashion, he found a way to combine the two. Instead of building barns and clearing meadows, he cleared a section of the farm for a compact golf course that would become notorious. He turned what had originally been a small irrigation pond into the central feature of his “Westridge Golf Course,” where four tee boxes and five greens—which he personally prepared and maintained—allowed the holes to crisscross the water nine times. He practiced almost daily on the course and then drew great pleasure in watching even his most experienced and skilled golfing friends freeze up when faced with the prospect of playing every single hole over a water hazard. There were very few who could match Cliff Gaddy on his home course. From his very earliest days in Danville, he was active in the city’s religious and civic life, serving in ways that went beyond his medical practice. Within a few years after his arrival in Danville, he received the Danville Junior Chamber of Commerce’s Outstanding Young Citizen award. He also was honored to be accepted early on into the Danville Rotary Club, which became the anchor of his civic commitment and the source of innumerable close friendships for decades to come. In the course of his over 50 years as a committed Rotarian he served in numerous capacities, including as president of the Danville Rotary Club. His extraordinary effort in launching Danville Rotary’s bone marrow registry drive was a particular source of pride. For that and his other service, he was honored as a Rotary International Paul Harris Fellow. He was raised as a Southern Baptist, and when he came to Danville he brought his own family into the family of First Baptist Church, where he remained a dedicated member and active lay leader for over half a century. His service in the church ranged from Sunday school teacher to chairman of the Board of Deacons. Clifford Garland Gaddy’s death marks the passing of the last surviving member of his immediate South Carolina family. He was the youngest child in a family of twelve. He was preceded in death by his parents, his four brothers, Sidney, Maston, Duncan, and Aaron, and his sister, Meta. Four other siblings died in infancy before he was born. He is survived by his children, Clifford Garland Gaddy, Jr., of Kensington, MD (Kerstin Tegin Gaddy), Charles Stephen Gaddy of Southern Pines, NC, Gary Douglas Gaddy of Orange County, NC (Sandra Herring Gaddy), Robert Lawrence Gaddy of Gloucester, VA (Evelyn Pilson Gaddy), Elizabeth Ann Gaddy Witman of Raleigh, NC (William David Witman), Janet Marie Gaddy of Brown’s Summit, NC (Timothy Moran), and Elizabeth Putney Gaddy of Rocky Mount, NC; his grandchildren, Benjamin Gaddy (Matney), Kristina Gaddy, Thomas Gaddy, Heather Garland-Gaddy Lycans (Jason), Erin Gaddy Meinhardt (Kurt), Anne Marie Gaddy Kriesel (John), Johanan Gaddy, Matthew Gaddy, Kimberly Colarik, Carson Bloomberg Lutchansky (Nathan), Austin Bloomberg (Chelsea), Carolyn Witman, Emma Witman, William Witman II, John Lea, Jeremy Lea (Kaitlin), Jason Lea, Jodi Lea, Ashley Moran, and Lindsay Elkins (Brian); and his great-grandchildren Sidney Gaddy, Lucy Lycans, William Lycans, Ari Meinhardt, Cooper Kriesel, Charlie Kriesel, Adrian Lutchansky, Parker Lutchansky, De’kimbe’ Lea, Jayden Lea, Henry Elkins, George Elkins, and Arthur Elkins. In the final phase of his life he was fortunate to enjoy the care of a group of individuals who exemplified the same dedication and selflessness he himself showed throughout his life and career. No one better represents the best of a new generation of caring physicians than Dr. Sydney Harris, and he deserves the deepest thanks. Sandra Allen, Jackie Lanier, Karen Thomas, Tina Martin, Nathaniel Payne, and Travis Carter became his friends, stayed with him until the end, and have earned the gratitude of all the surviving members of his family. Besse Waller and the other wonderful caregivers who were with him at the beginning of his care are also remembered by the family. The family offers special thanks to Commonwealth Home Nursing and Hospice and to Liberty Homecare and Hospice for their support during Dr. Gaddy’s final months. Dr. Gaddy was always a dedicated supporter of hospice services in Danville. The Memorial/Celebration of Life service for Dr. Clifford G. Gaddy will be at First Baptist Church in Danville, VA, on Sunday, July 23, at 2:00 PM with the Reverend John Carroll officiating. The family will receive friends from 1:00 PM to 2:00 PM at First Baptist in the Heritage Room before the service. In lieu of flowers, the family requests that friends consider donations to two organizations that had special meaning for Dr. Gaddy: First Baptist Church Memorial Fund (871 Main St., Danville, VA) and Danville Life Saving Crew (202 Christopher Ln., Danville, VA). Dr. Gaddy requested his body be contributed to the Virginia Anatomical Society for teaching and research.

To order memorial trees or send flowers to the family in memory of Clifford Gaddy, please visit our flower store.

Service Schedule

Past Services

Visitation

Sunday, July 23, 2017

, 871 Main Street , Danville, VA 24541

Service

Sunday, July 23, 2017

, 871 Main Street , Danville, VA 24541

Photo Gallery

Guestbook

Visits: 0

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the

Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Service map data © OpenStreetMap contributors